What Kind of Consumer Is a Human When They Eat the Beef Out of a Patty

Consumers' Perceptions and Sensory Properties of Beefiness Patty Analogues

1

Department of Food Science, University of Otago, P.O. Box 56 Dunedin, New Zealand

two

Department of Food Science and Nutrition, College of Food and Agricultural Sciences, King Saud University, Riyadh 11362, Saudi arabia

*

Author to whom correspondence should exist addressed.

Received: 4 December 2019 / Revised: 3 January 2020 / Accepted: 4 January 2020 / Published: 7 Jan 2020

Abstract

The nowadays written report was carried out to gain consumer insights on the utilize of tempeh (a fermented soy bean production) to better the healthiness of beef patties and to determine the acceptable level of tempeh (ten%, 20%, or 30%) in the patty. The study consisted of conducting ii focus groups (north = xv), a pilot sensory evaluation, and a total consumer sensory study. The focus groups were asked near their consumption of beefiness patties, attitudes towards processed meat, attitudes towards negative aspects of red meat consumption, and attitudes towards tempeh consumption, likewise as sensory perceptions of the cooked patties and their visual credence of raw patties. Focus group discussions suggested that there was a marketplace for the production if consumers were informed of tempeh health benefits. Participants seemed more willing to cull how to balance their diet with an antioxidant source than buy a beef patty with added antioxidants. The focus group participants rated the visual attributes of raw patties from all treatments and it was institute that the twenty% tempeh and thirty% tempeh patties were ranked lower (p < 0.05) than the others. Overall, the sensory experiments showed that the inclusion of 10% tempeh was the almost acceptable level of addition. There were no significant (p > 0.05) differences between the control and 10% tempeh patties for overall acceptability or acceptance of flavour. However, x% tempeh patties were found to be more than tender and juicier than the control (p < 0.05). A proper knowledge and awareness of consumers about the benefits of tempeh could permit the development of beef containing tempeh products.

i. Introduction

Ruby-red meat has been consumed past humans for thousands of years and has played an important part in human evolution. It is a nutrient-rich food which is high in poly peptide; minerals, such as iron, zinc, and selenium; and many vitamins [1]. Nevertheless, in contempo years, there has been a negative consumer reaction to red meat [2]. This has partially been due to its saturated fat content, just besides due to the causal link between scarlet meat consumption and the incidence of colorectal cancer. Cerise meat was plant to be correlated with the gamble of having colon cancer, whereas fish intake was not associated with the run a risk and a slight negative association was observed with poultry consumption [3]. The difference between meat types and run a risk of colon cancer could be due to the high levels of haem in red meat. The catalytic activity of haem iron in promoting oxidative processes may be linked to colon cancer formation. Sesink et al. [4] found that fatty lonely did not bear on the levels of cations found in feces; notwithstanding haem increased fecal cation concentrations in low, medium, and high fat diets, which demonstrates that haem in the presence of fat impairs the absorption of cations and causes epithelial damage. There was a pregnant interaction (p < 0.001) betwixt haem and fat, which affected the fecal cation concentration [iv], supporting a hypothesis for a haem-induced lipid oxidation mechanism as a potential contributor to colon cancer. Much inquiry has been conducted to investigate the add-on of non-meat additives or extenders to amend nutritional properties [5,half-dozen,7,eight,9,10,11,12,xiii], shelf life [14,15], sensory properties [5,16], and physical parameters [5,16] and brand apply of by-products of other food industries [5] to improve the quality of meat patties.

Partial substitution of meat by plant products is regarded as an emerging strategy to reduce meat consumption [17,18] and ameliorate the healthiness of meat products. This strategy is successful and accustomed by consumers considering it is not aiming at eliminating meat from the diet, but targets the implementation of simple adjustment of the products without compromising important attributes desirable in meat [nineteen]. The sensory properties of meat products substituted with establish products are important for the acceptability of products. In particular, gustation and texture are highly of import characteristics for acceptance [xx,21]. The format of the meal [21] and echo exposure [22] are important for the acceptability of meat substitutes and meat analogues (meat products where a portion of the meat is substituted by some other food ingredient, also known every bit hybrid meat products). Evaluations of meat products substituted with plants [21] or insects [23] accept indicated the potential of achieving the same level of acceptability by consumers, but gender differences may be.

Consumers have go increasingly concerned virtually fat consumption and have frequently associated reddish meat with a loftier fat content. There are several classes of fat and each contributes differently to the gamble of cardiovascular disease [24]. Cardiovascular disease is associated with atherosclerotic plaques which build upwards on the within of coronary arteries that provide blood to the heart musculus (myocardium) [25]. These plaques are mainly composed of cholesterol and low density lipoprotein (LDL) particles, which are the primary cholesterol carriers. Low density lipoproteins are oxidized and consumed by macrophages [25], which can consequently lead to increased oxidative stress and diseases. The objective of this report was to gain insights on consumers' perception of the addition of tempeh to beef patties with the aim of producing a healthier beef product, past conducting focus groups, as well every bit airplane pilot and full consumer sensory trials.

ii. Materials and Methods

All experiments were canonical by the University of Otago Human Ideals commission (09/156).

The experiment design included the following:

- (1)

-

2 focus groups (n = fifteen) of subjects that were screened (Section 2.3.one) before joining the focus groups. The focus groups explored the panelists' attitudes towards the consumption of beef patties, their knowledge of processed meat products, a sensory evaluation of beef patties containing tempeh, and their perception of the new beef analogue after providing information on the health benefits of including tempeh in the product;

- (ii)

-

pilot sensory analysis study (due north = xiv) to decide the optimum tempeh % (10%, 20%, or 30%) to include in a full-scale consumer sensory study;

- (3)

-

Consumer sensory written report (n = 118) to determine consumers' perception and acceptability of beefiness patties containing ten% tempeh compared with a control (100% beef) and a comparably reduced beef patty that contained 10% bread crumb.

2.1. Sample Training

Soy beans (Glycine max) were purchased locally from the Sense of taste nature organic shop (Dunedin, New Zealand) and were soaked for 2 days at 4 °C. The beans were cooked for 10 min in a pressure cooker at 100 °C, tuckered, dried in towels, and treated with white vinegar at a concentration of 2 mL/100 g of beans. A starter culture (Rhizopus oligosporus) was then added at a concentration of 1 g civilization/kg beans. The mixture was packed in perforated ziplock bags (170 × 180 mm) and incubated in a snaplock container (Klip it, 255 × 120 × 55 mm, 1.75 Fifty, Sistema Plastics, New Zealand) with i Chiliad potassium nitrate solution to create a humid atmosphere (92% relative humidity) at 31 °C in an incubator (Labserve, Ontherm Scientific Ltd., Hutt Metropolis, New Zealand) for 24 h. The produced tempeh was vacuum packed and frozen at −80 °C for farther use.

Fresh beef semitendinosus muscles (ST; middle of round, n = half dozen with total weight of 22 kg) of a normal pH (range 5.55–5.64) were obtained from a local supplier (Alliance Wholesale meats, Dunedin). The meat was separated into lean and fat and and so diced. Diced meat and 10% fat were added to a Kenwood blender with a mincing zipper (Alp 5 blade and mincing plate, 4.5 mm diameter die). The patties were prepared (nigh 4–5 kg for each treatment) as described in Table 1. Five experimental groups (Tabular array ane) were as follows: not treated command sample (control); samples with 10% of the weight replaced with 10% bread crumb (Staff of life crumb ten%); and samples with part of the weight replaced with tempeh at the level of ten% (Tempeh 10%), 20% (Tempeh twenty%), or thirty% (Tempeh 30%). Patties were made past shaping 120 g of the mixture with a patty former. Fresh samples were used for colour stability trials and other analyses, and the patties were vacuum packed and stored at −80 °C.

2.2. Focus Grouping

Consumer perceptions, including attitudes and sensory perception, are important characteristics of a patty. Focus groups were used for exploratory inquiry to obtain consumers' insights on the use of constitute materials to improve the healthiness of beef patties, decide the level of tempeh inclusion, and serving conditions (preference for at home utilize vs. take out). This information was used later in designing the consumer sensory analysis and to investigate consumer attitudes towards a novel product such every bit beef patties containing tempeh.

A focus grouping is an interview based on a fix of predetermined open up ended questions which aims to generate discussion among participants to proceeds insights into consumer behavior [26]. Information technology is based on a pocket-sized number of issues, with the aim of understanding how the behavior of individuals is influenced by their beliefs, attitudes, and feelings [26,27,28].

2.2.1. Participant Recruitment

Flyers were used to recruit participants for two focus groups. They were placed around the University of Otago and Otago Polytechnic campuses, at supermarkets, a public library, and fish and chip shops. Flyers were placed over a period of 2 weeks and 15 participants were called in total to take part in two focus groups later a brief screening over the phone. Respondents were screened based on three questions, in order to exclude those who would non be eligible for the focus group. The questions were as follows:

-

Are y'all willing to participate in a recorded discussion on this topic? The recorded data will exist handled ethically co-ordinate to the academy policy on private information;

-

Do y'all have whatsoever upstanding or religious objections to eating beef?

-

Are you allergic to gluten and/or soy?

Participants who answered yes to question one and no to questions two and 3 were invited to participate in the focus groups.

The offset focus groups attempted to comprehend the research aspects from diverse age and professional groups, whereas the 2d focus group sought the opinions of young academy students as it was clear that they correspond a large fraction of consumers. The characteristics of the focus group participants are shown in Tabular array 2.

ii.ii.2. Arrangement of the Focus Group

The focus groups were held on two separate days. The durations of the two focus groups were ninety minutes and eighty minutes for the beginning and second focus groups, respectively. The focus groups were moderated by the authors. The focus group sessions were held in a sensory lab to encourage interaction and allow for the best audio recording environment. A tape recorder with an external microphone was used to tape the answers of participants. Participants read an information canvas and signed a consent form before the sessions. The participants engaged in an ice-breaker discussion with each other and with the moderator for five minutes before the focus group officially started. The focus grouping session was divided into five parts and guided by the focus grouping protocol. At the decision of the focus group, participants put their name in a basket for a random draw for a prize of a $l grocery voucher.

2.2.3. Sample Preparation

The v patty treatments were prepared as described in Section 2.2. Patties were then placed in a fridge at 4 °C on a tray lined with wax paper; wax paper was put on the surface to preclude drying until they were later cooked on the aforementioned day. One patty of each formulation was also placed on polystyrene trays wrapped with glad wrap and stored at 4 °C in a refrigerator until they were later on shown to participants for an evaluation of raw patties. The patties were cooked in canola oil on a Kambrook Banquet electric fry pan for two minutes on each side. They were then put into a fan forced oven for x minutes at 180 °C, which was sufficient to produce an internal temperature >75 °C. The patties were removed, cut into quarters, and wrapped in aluminium foil. They were put into labelled trays and held in an oven at 80 °C until serving within 4–v min from grooming.

2.2.4. Focus Group Protocol

The focus group protocol consisted of v parts that dealt with the consumption of beef patties, attitudes towards processed meat, attitudes towards negative aspects of cerise meat consumption, and attitudes towards tempeh consumption, besides as sensory perceptions of the cooked patties and visual acceptance of the raw patties.

Office one: Attitudes Towards the Consumption of Beef Patties

The first set of questions was about the participants' normal consumption habits with regards to takeaways, peculiarly beef patties "commonly known as burgers". Participants were asked near when and where they commonly consume beefiness patties/burgers and what factors influenced their choice of takeaways and/or burgers.

Part 2: Consumer Perception and Knowledge of Processed Meats

At the outset of this section, the participants were shown an information canvass on candy meat and the addition of not-meat ingredients to meat products. This department was important for evaluating the consumers' noesis of meat extenders and their attitude towards products containing not-meat components every bit patties may contain up to xxx% tempeh. Questions were aimed at exploring whether participants realized how many non-meat ingredients are included in processed meat, understanding why producers practise information technology, and if it seems deceptive or not.

Part three: Preliminary Sensory Analysis

During this part of the session, the participants analysed the patties for sensory attributes. Quarter sections of patties, temperature tested with a thermometer, were brought from the warming oven in a divide kitchen and were simultaneously served equally 3-digit coded samples to participants. The attributes assessed were the intensity of beefiness odor (slight–strong), intensity of other (non-beefiness) aroma, tenderness (tough–tender), juiciness (very dry–very juicy), chewiness (very chewy–very soft), beef flavour intensity (very slight–very strong), intensity of other (non-beef) flavor (very slight–very potent), credence of flavor (dislike extremely–like extremely), and overall acceptance (dislike extremely–like extremely). Attributes were rated on paper ballots with 5-signal give-and-take-anchored scales, with the exception of acceptance of flavor and overall acceptance, which were assessed on seven-point discussion-anchored scales. This section served as exploratory research for sensory analysis to choose an acceptable level for tempeh inclusion in a patty.

Part 4: Effect of Information of Health Benefits on the Consumer Perception of Novel Beefiness Patties

This section began past providing participants with an information sheet on published research suggesting the negative aspects of red meat consumption [29] and potential wellness benefits of tempeh [30,31]. The objective was to see how wellness information impacts attitudes towards adding a vegetal antioxidant source to the beef patties. Questions during this section were based around previous knowledge of a link between ruby meat and cancer and if this link led to a change of diet. Participants were also asked if this would increment their likelihood of eating meat with an antioxidant source and if they had tried tempeh. Participants were asked whether they would make an attempt to consume antioxidants with cherry meat as a separate part of a meal or whether the inclusion of the antioxidant source (such as in the tempeh) in a patty would be a user-friendly option. They were too asked if they would be willing to purchase a patty containing tempeh.

Part 5: Evaluation of Raw Beefiness Patties

One patty of each formulation (freshly prepared) was displayed to participants in raw form on a polystyrene tray, as it would usually be presented for retail sale. The objective was to determine the attitudes towards the product in the form it would be sold at retail after the health data had been given. This was decided to be a better method for assessing the purchase intention than consumption of the cooked patties alone, every bit consumers base meat purchases on visual cues [32,33].

ii.two.5. Focus Group Analysis

The focus group discussions were recorded with Audacity software (version 1.2.half-dozen) and were later transcribed. Participants and responses were coded and the transcripts were analysed by sorting participant quotes thematically according to the insights they provided into consumer attitudes, in society to write the discussion.

ii.3. Sensory Analysis

2.3.1. Airplane pilot Sensory Analysis Report

A smaller airplane pilot sensory study (n = fourteen) was carried out earlier a full-scale sensory study in guild to assist in the design of the larger experiment. Participants were students and staff members from the University of Otago.

2.three.ii. Consumer Sensory Analysis Study Recruitment

The panelists for sensory analysis (north = 118) were recruited by different contact and advertizement methods. The sample size is considered adequate to avert type I and type Two errors that tin can arise in a consumer sensory exam [34]. Panelists were recruited from a database kept by the Food Science Department, University of Otago and from fliers placed around the University campus, Otago Polytechnic campus, and halls of residence; an ad at lectures; and by emails circulated by the administrators of academy departments. Respondents bundled a fourth dimension to come in and taste the beefiness patties and were asked a prepare of questions to screen out participants unable to participate based on personal behavior, allergies, or a lack of familiarity with the product. The gender and age categories of panelists are shown in Table three.

Study Design:

The questionnaire for participants was created in Compusense V (version 4.8.eight, Guelph, Ontario, Canada). The panelists were asked to declare their age and gender categories and for each sample question, they were asked for the attributes of overall acceptability, intensity of beef odour, tenderness, chewiness, juiciness, intensity of flavor, level of non-meat flavor, and acceptance of flavor. After answering these questions for all samples, the consumers were asked most the frequency of beef patty/hamburger and soy production consumption.

Sample Preparation:

Samples were prepared as described in Section 2.1 higher up for the focus groups. The results obtained from the focus groups and airplane pilot sensory studies guided the treatments chosen for consumer sensory assay, which included a command, and 10% bread crumb- and x% tempeh-containing patties. The samples were prepared i week before the sensory analysis, frozen at −20 °C, and defrosted in a fridge overnight prior to the sensory assay. The defrosted patties were cooked as described for the focus groups to a higher place. After cooking, they were cut into quarters, wrapped in tinfoil, and placed in goulash dishes within an oven set to 100 °C.

Sensory Analysis:

The analysis was performed in sensory booths in the Sensory Scientific discipline Enquiry Heart at the Food Scientific discipline Department of the University of Otago. Participants start read an information canvas and signed a consent class and were so served the samples. The samples were coded with randomized numbers according to the serving order devised by Compusense. The samples were served under ambient light in booths under positive pressure. Participants took one minute breaks and drank water between assessing samples to cleanse their palettes.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The sensory data from the focus groups and airplane pilot sensory study were analysed using a Kruskal–Wallis examination (Minitab 16, Minitab, State College, PA, USA). A statistical analysis of sensory attributes obtained in the consumer sensory report was performed as a ane way analysis of variance (ANOVA), with treatments as the independent variable, and significant differences were detected at a level of p < 0.05, identified by post hoc Tukey tests using Minitab software version 16 (Minitab, State Higher, PA, USA).

iii. Results and Give-and-take

3.1. Focus Group

The focus groups were coded for ease of word (Supplementary Tabular array S1). The main letters from the focus groups are discussed in the following themes.

iii.1.one. Consumption of Takeaways

Most focus group participants consumed takeaways at least once a week and the younger university students more often than not consumed takeaways more oftentimes. The proximity of the takeaway outlet and the price seemed to exist the nearly of import factors for an increased consumption of takeaways. Young consumers were reported to be the most frequent takeaway consumers, despite their belief that takeaway food is unhealthy [35]. Younger adult participants take been reported to be more frequent consumers of takeaways than older adults, possibly due to a more positive perception of convenience foods [34,35]. Total fourth dimension workers consumed takeaways twice equally oft as non-full fourth dimension workers [35], although this was non the instance in this focus grouping written report.

Two of the second focus group consumers said that they commonly buy beef patties/burgers at fast food outlets. Although, in the groups, in that location was a majority of fast food hamburger consumers, amongst some of the participants in both groups, there was a definite preference for homemade burgers. For example, P2G1 stated that "they just sense of taste nicer unremarkably, homemade patties and stuff", and P9G2 expressed, "But, I love homemade hamburgers the all-time". One of the reasons mentioned for this is that it was a "pretty easy meal to prepare" (P2G1) and "quite filling likewise" (P1G1). In the second focus grouping the reason for making bootleg burgers were that "it tastes mode better" (P10G2). There was a noticeable lack of trust in fast food outlets for some of the young female consumers. I reason given for this lack of trust was "considering I know what's inside" (P15G2), as the participant studied Homo Nutrition papers and had a knowledge of some ingredients used in beefiness patties and their nutrient contents. Another did not trust that burgers were fabricated from the ingredients that they were claimed to exist made from: "with mince you lot know it is mince…rather than I don't know like in craven burgers, you know is it actually craven" (P10G2).

For ane participant, it was previous work in the fast food industry which influenced their beliefs: "You know, how long the meat sits there" (P9G2). Female consumers preferred to eat burgers from the higher quality takeaway outlets and i stated that they would exist "… willing to pay a bit more than for a really good burger" (P4G1). For the desirable attributes of the hamburgers, younger females placed more emphasis on health, whilst the male consumers did not. I male participant said, "I don't think that healthy comes into it when I swallow hamburgers personally" (P1G1). Conversely, two female consumers cited wellness as ane of the desirable attributes for a burger. The meat content was also stated as being of import: "I definitely remember that all meat kind of burgers not like probably 30% meat and the rest is other things" (P15G2).

The consumption of fast food and takeaway food represents a existent paradox equally consumers by and large find this food to be unhealthy, but its consumption is increasing [36,37,38]. For instance, in a previous study, 78% of Americans considered fast food as "non at all good or not too good", but more than than half of Americans were reported equally eating fast nutrient at least once a week [36]. The main reasons reported for the frequent apply of takeaways and fast nutrient outlets are their convenience, low cost, consistent gustatory modality, and easy admission, since many outlets are found in localities [36,37,38].

3.ane.two. Adding Non-Meat Ingredients and Processed Meat

Overall, the participants were quite skeptical about processed meat and related this to the profiteering of producers: "They are non adding ingredients because they want to make a consumer happy (but) considering they see that they can add value to the product" (P6G1). European consumers accept besides expressed the view that meat processors only work for their benefit, rather than that of the consumer [39]. Some consumers have this equally a manner of getting lower priced meat products and are not so concerned. The younger male students in the second focus group are in this category. These products were recognised every bit a way of selling second-grade meat, which is in agreement with the perception of European consumers [39], although some consumers accept this every bit part of buying cheaper meat products. Overall, the preference was for non-candy meat forms and was similar to that of the consumers interviewed past de Barcellos et al. [39]. For the second focus group, the word processed had especially negative connotations: "I don't think I accept e'er bought the frozen patties considering I just think they expect then yuck… like information technology just looks so processed" (P9G2). Additionally, 2 of the consumers were influenced past having grown up with home-killed meat on a farm.

3.i.3. Sensory Testing of the Beef Patties

Ane of the panelists was very familiar with tempeh, whilst most were not and used a diversity of words to describe the flavour that was strange to them. It was described equally "vegetablely" (P2G1), and smelling like "warm pecans" (P4G1) or having a "beaniness" (P4G1).

3.1.4. The Link Between Red Meat and Colon Cancer

A couple of the panelists had previously heard near a link between carmine meat and cancer. One was a Human Nutrition student, but was more than familiar with the link of heterocyclic amines and processed meats to colorectal cancer. Overall, the panelists were quite skeptical about this link as there were many factors reported as existence linked to cancer in the media. In the two separate groups, panelists said, "everything causes cancer these days" (P1G1) and "only they link everything to cancer" (P10G2). Participants more often than not did not care or were not willing to change their consumption habits due to this fact and one panelist said, "it'southward more dangerous to dye your hair" (P8G2). This is in contrast to a carve up written report, which found that beefiness consumers were quite health conscious [40], although this study had a more varied historic period construction. The previous written report investigated European consumers and establish that a number of consumers had concerns virtually beef carcinogenicity and its long-term health furnishings [twoscore].

3.ane.v. Consuming Patties with an Antioxidant Source or Balancing Yourself

Participants seemed more than willing to balance their diet with an antioxidant source than purchase a beefiness patty with added antioxidants. Some participants perceived this every bit unnatural and said, "Unremarkably I would rather, I retrieve, buy something more natural" (P14G2) and "I don't want people chopping and changing my nutrient" (P11G2). Consumers react negatively towards a perceived 'interference' with nutrient products, including the manipulation of beef, which is perceived as 'unnatural' and may explain these answers [39,xl,41,42]. The ability to sell tempeh patties may be enhanced by the inclusion of a health merits on the packaging equally these claims are able to positively influence the consumer perception of a health benefit [43].

However, frequent takeaway consumers are significantly less likely to attempt to attain dietary requirements of fruits and vegetables [44], which may make it more difficult to sell tempeh patties through a takeaway outlet. This was stated by the participants: "to get to eat to McDonalds to have a good for you hamburger, it seems a bit paradoxal" (P6G1). Participants expressed that a potential consumer would need to be informed of the health benefits in order to be willing to purchase the product: "If yous outlined the ingredients its all like, you need to have that in information technology maybe, otherwise it would be like why alter?" (P8G2).

3.1.6. Consuming Tempeh

There were contrasting attitudes towards consuming tempeh. Three of the participants had tried it, only those who had non were generally not accepting of the description of tempeh. The description was unappealing for younger consumers non familiar with the product and elicited responses such as "That doesn't sound adept" (P14G2) and "that doesn't sound appealing" (P9G2). For an idea of what tempeh was, two participants asked if it was like to tofu. Food neophobia has a negative event on the credence of functional food products such every bit beefiness patties containing tempeh [45]. Food neophobia was non explored in this focus group; all the same, these consumers may be more than neophobic than the public in general. Food neophobia in this group could be due to a lack of exposure to novel and foreign foods.

3.1.vii. Evaluation of the Beef Patties

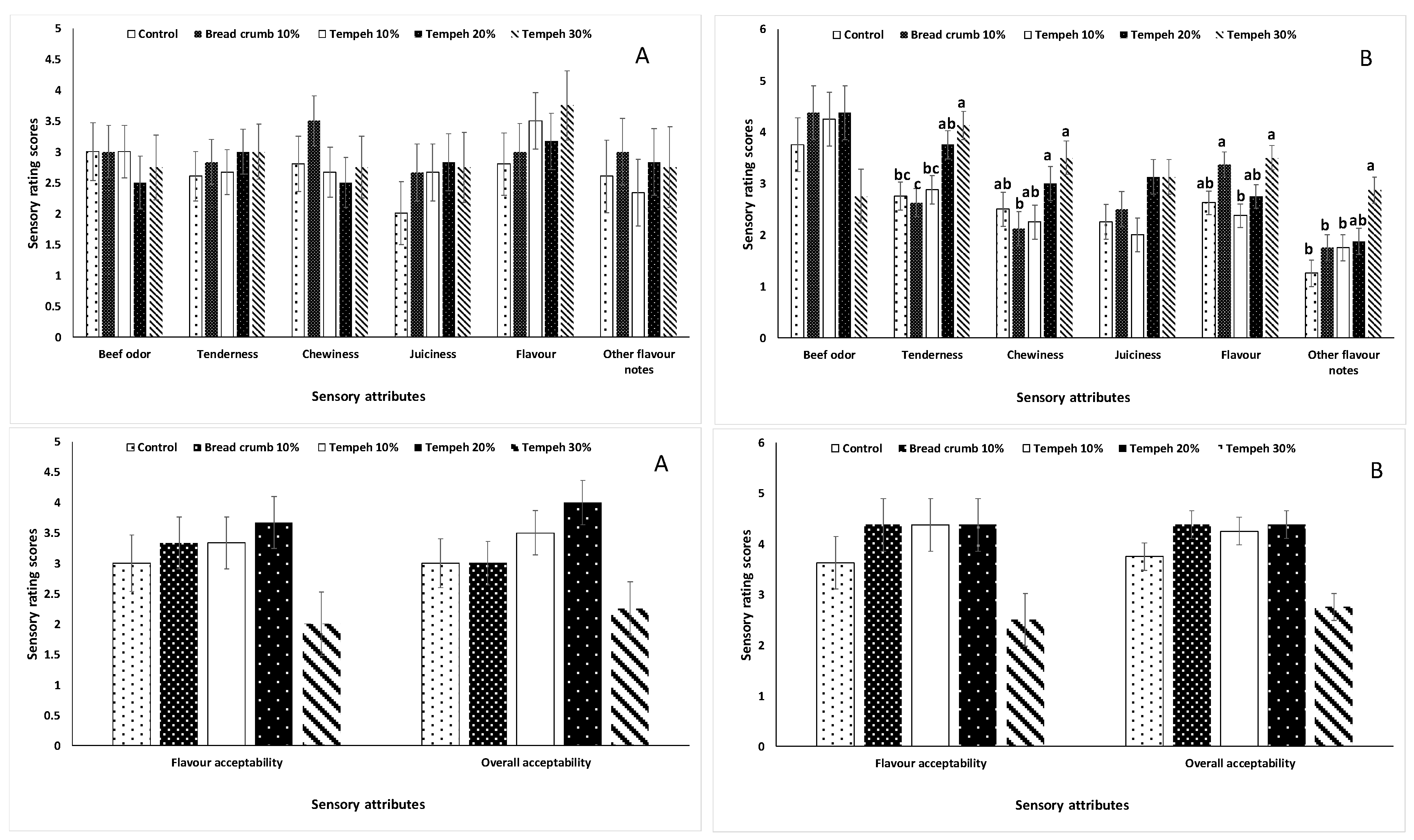

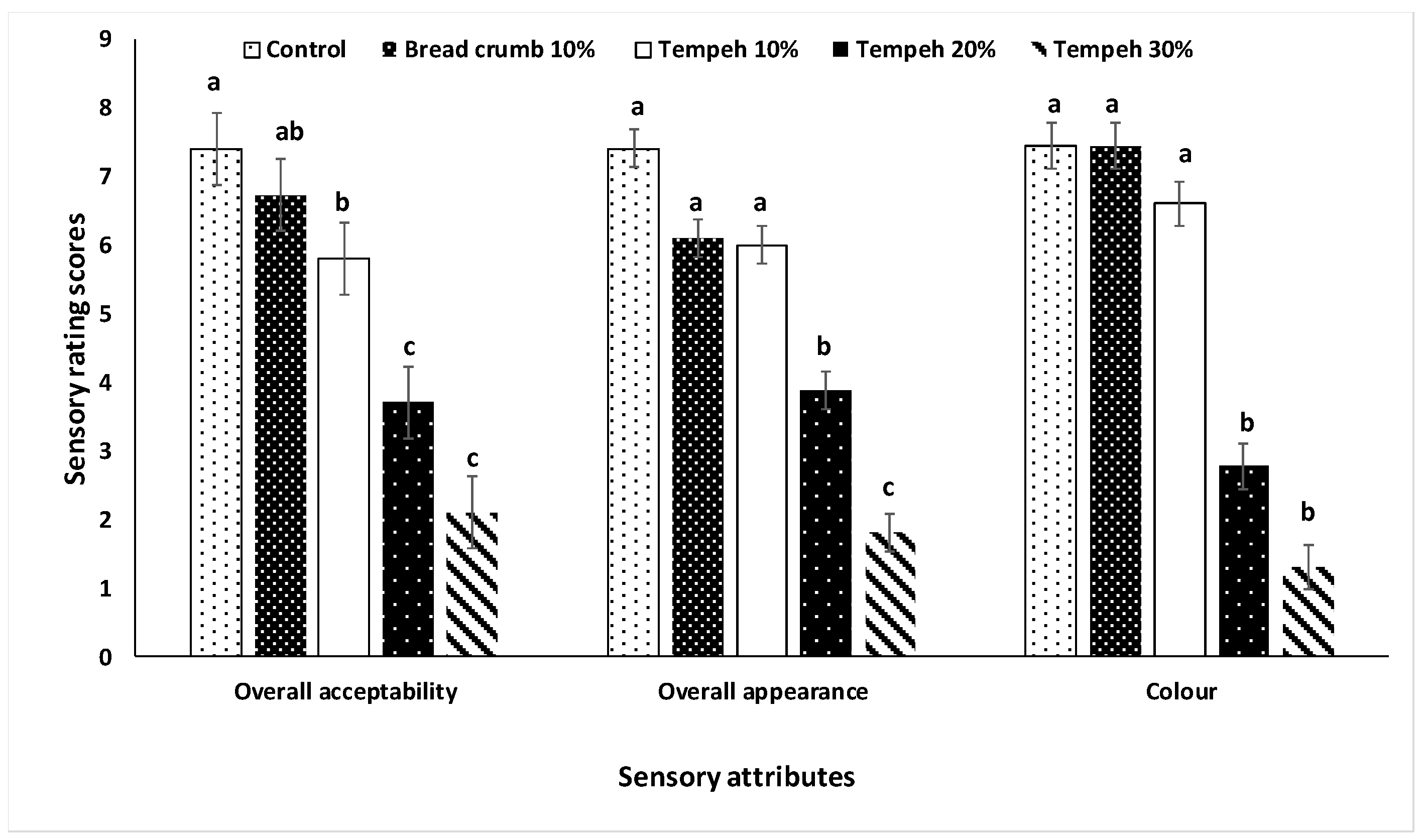

The first focus group did not find any differences among all the samples (Figure 1A). For the 2d focus group, in that location were significant differences in the tenderness, where the 10% bread nibble was found to exist chewy and the least tender, and the xxx% tempeh was perceived to be soft and the about tender (Figure 1B). There was no difference (p > 0.05) in the intensity of beef season amongst all treatment groups (Effigy 1A,B). The participants were asked to choose and charge per unit visual attributes of raw patties from all treatments. The 20% tempeh and 30% tempeh patties were consistently rated lower (p < 0.05) than the others (Figure 2). The 10% tempeh patties were non different (p > 0.05) from the x% breadstuff crumb patties and were not significantly different from the control in terms of color or appearance.

There is a relatively large subtract in ratings of visual attributes when increasing tempeh incorporation from 10% to 20% (Figure 2). Ratings of appearance are important as this aspect influences consumer purchase decisions [29,xxx]. Data from the second focus group suggests that tempeh 10% is the tempeh-containing patty most likely to exist purchased. A pilot sensory written report was necessary post-obit the focus groups, in order to provide a larger sample size to select an appropriate patty.

three.2. Pilot Sensory Study

From the pilot sensory study, information technology was observed that the ten% tempeh patties had rating scores closer to the control than xx% and 30% tempeh, regardless of significance (Tabular array 4). Most importantly, they were closest in overall acceptability and there were decreased ratings with additional tempeh incorporation (Table 4). This evidence, combined with the focus grouping quantitative data, which suggested that ten% tempeh patties were the about like to the control, led to the decision to take the 10% tempeh patty to the full consumer sensory trial. The x% tempeh patty was more likely to be accepted and less likely to have significant differences in sensory attributes in the larger sample size of the full-size sensory trial than patties containing higher levels of tempeh incorporation.

3.3. Consumer Sensory Report

Differences were perceived by participants in terms of flavor and texture sensory attributes, merely not for overall hedonic attributes. Hateful sensory scores of participants for the overall acceptability and credence of flavour did non significantly (p > 0.05) differ between the iii beefiness patty treatments (Table 5). The overall acceptability values were lower than in some previous studies with other extenders for tempeh-containing patties [11,46,47]. The substitution of ten% tempeh was more acceptable than the substitution of 3% tomato plant peel, ii% hazelnut pellicle, or nine% flaxseed flour [5,8,ten]; however, it was similar to the substitution of x% okara powder, an olive oil/corn oil/fish oil blend, 0.v% carrageenan, 6% olive cake, or 7.5% okara, which did not affect the overall acceptability of beef patties [8,eleven,46,48,49].

The acceptance of tempeh patty flavor was higher than that for patties extended with 4% hazelnut pellicle or 37.5% wet okara, only lower than that for patties extended with carrageen, textured soy poly peptide, tri sodium phosphate, or 10% plum puree [10,11,12,46,47]. Fractional commutation of the fatty with an olive oil/corn oil/fish oil blend or 3% flaxseed flour similarly did not significantly touch on the acceptability of flavor [8,48]. Decreases in flavor acceptability have been observed with the substitution of iii% hazelnut pellicle, 1.v% texturized soy protein, 30% wet okara, and 6% flaxseed flour, and increases have been recorded with the addition of ten% plum puree [8,12,46,47]

Like to tempeh-containing patties, there were no meaning differences in the perception of intensity of beef odour with 15% date cobweb [xiii].

The command was higher (p < 0.05) in terms of beef odor than both 10% staff of life nibble and x% tempeh (Table 5). Despite the lower beef scent, the overall flavor intensity of 10% breadstuff crumb and 10% tempeh did not differ from the command (Table 5).

The ten% staff of life nibble treatment was rated the most tender, followed past x% tempeh and then the control, and all were significantly (p < 0.05) different (Table 5). This is in agreement with literature where increased tenderness occurred with the improver of fifteen% date fiber and 10% carbohydrate-lipid composites [thirteen,50]. The same trend was observed for chewiness. Juiciness was rated the highest for ten% tempeh, while the control was rated significantly (p < 0.05) lower and 10% breadstuff crumb did non differ significantly (p > 0.05) from either treatment (Table 5). Increases in juiciness with a ten% exchange of sugar-lipid composites or x% tomato paste have also been reported [50,51]. However, the substitution of up to 30% sorghum flour did not produce whatsoever pregnant difference in juiciness [52]. The use of soy edible bean products in beefiness products has been extensively investigated to improve the healthiness of beefiness products, improve the production economics, or modify the sensory attributes of the products. The use of textured soy protein (TSP) or soy protein concentrate (SPC) at a exchange level of twenty% or 30% in beefiness patties was investigated using a consumer panel and a family consumer panel [53]. The 20% TSP-containing beef patties were rated like to whole beef patties and the scores for both of these treatments were college than those found with 30%TSP, and xx% and 30% SPC treatments [53]. Similarly, substitution beef patties with 20% or 30% TSP did not bear on consumers' acceptability, despite the formation of a beany flavor and taste caused by the TSP addition [54]. Additionally, the use of TSP at 25% did not affect the flavour of beef patties [55]. Contrary to these findings, the use of 15% or xxx% hydrated TSP in beef patties was found to reduce the beefiness flavor and overall acceptability of the patties [56], only improved the tenderness of the patties. The same trend was reported for 20% hydrated soy bean [57]. Overall, the various results reported above are likely to be related to differences in the soy edible bean product, the add-on level, and possibly the background of the consumer console. Unlike many of the studies mentioned above, which used trained sensory assessors [8,x,11,12,13,46,47,50,51,52], this study used a larger untrained consumer sensory trial, which is important for testing the market potential.

iv. Conclusions

Information from the focus group suggested that consumers are not very concerned with a link between cherry-red meat and colon cancer, although several participants had heard of this link. They were skeptical most the media reporting of cancer risks. This gives the impression that there is little potential market place for a novel product, such every bit the tempeh patty; nonetheless, the participants were mainly young people, who probably did not have much consideration of a healthy diet. Quantitative data did not testify corking differences between the patties tested. For appearance, nonetheless, x% tempeh patties were rated closer to the control and bread nibble patties, which suggests that they are more than likely to exist purchased than other tempeh-containing patties. The x% tempeh patties had meliorate eating properties. For example, these patties were more than tender, juicier, and had more flavour, but they were lower in the intensity of beef odour.

Overall, the 10% tempeh patty was the tempeh-containing patty with the about positive attributes. It was not significantly different than a control patty for overall credence and acceptability of flavor and is comparable to a control for visual attributes and more acceptable visually than patties containing more than tempeh. The present report did non investigate the impact of tempeh substitution on the volatiles and season of the cooked beef patties and future piece of work will address this event.

Supplementary Materials

The following are bachelor online at https://www.mdpi.com/2304-8158/nine/1/63/s1, Table S1: Focus group themes for the consumption of takeaways, noesis of the addition of additives to candy meat products, and human relationship betwixt colon cancer and the consumption of processed meat products.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.T., I.A.Yard.A., F.Y.A.-J., and A.Eastward.-D.A.B.; methodology, J.T., I.A.One thousand.A., and A.E.-D.A.B.; formal analysis, J.T. and A.E.-D.A.B.; investigation, J.T., and A.Due east.-D.A.B.; resources, F.Y.A.-J., and A.E.-D.A.B.; data curation, J.T., and I.A.Thousand.A.; writing—original typhoon preparation, J.T., and A.E.-D.A.B.; writing—review and editing, all authors; supervision, A.East.-D.A.B.; funding acquisition, I.A.M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors extend their appreciation to the International Scientific Partnership Program ISPP at King Saud University for funding this research work through ISPP-16-73(ii).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Farouk, 1000.M.; Yoo MJ, Y.; Hamid, North.S.; Staincliffe, Thousand.; Davies, B.; Knowles, S.O. Novel meat-enriched foods for older consumers. Food Res. Int. 2018, 104, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusch, S.; Fiebelkorn, F. Environmental bear upon judgments of meat, vegetarian, and insect burgers: Unifying the negative footprint illusion and quantity insensitivity. Food Qual. Prefer. 2019, 78, 103731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannucci, Due east.; Rimm, E.B.; Stampfer, M.J.; Colditz, Thousand.A.; Ascherio, A.; Willett, W.C. Intake of fat, meat and cobweb in relation to risk of colon cancer in men. Cancer Res. 1994, 54, 2390–2397. [Google Scholar]

- Sesink, A.L.A.; Termont, D.Due south.M.50.; Kleibucker, J.H.; Van der Meer, R. Red meat and colon cancer: Dietary haem but not fat, has cytotoxic and hyperproliferative effects on rat colonic epithelium. Carcinogenesis 2000, 21, 1909–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M.L.; Calvo, M.One thousand.; Selgas, Thousand.D. Beef hamburgers enriched in lycopene using dry tomato peel as an ingredient. Meat Sci. 2009, 83, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danowska-Oziewicz, M. Nutritional quality of low-fat pork patties manufactured with the utilise of soy protein isolate. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 45, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, E.H.; Khalil, A.H. Characteristics of depression fatty beef burgers as influenced by various types of wheat fibres. J. Sci. Food Agric. 1999, 79, 493–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilek, A.East.; Turhan, S. Enhancement of the nutritional status of beef patties by adding flaxseed flour. Meat Sci. 2009, 82, 472–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzudie, T.; Scher, J.; Hardy, J. Common bean flour as an extender in beef sausages. J. Food Eng. 2002, 52, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turhan, Due south.; Sagir, I.; Ustun, Due south. Utilisation of hazelnut pellicle in low-fat beef burgers. Meat Sci. 2005, 71, 312–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turhan, Due south.; Temiz, H.; Sagir, I. Utilisation of wet okara in depression-fat beef patties. J. Musculus Foods 2006, 18, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turhan, S.; Temiz, H.; Sagir, I. Characteristics of beef patties using okara pulverisation. J. Muscle Foods 2009, 20, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, I.B.; Khalil, A.H. Quality characteristics of beef patties extended with date fibre. In Proceedings of the 54th International Briefing of Meat Science and Technology, Cape Boondocks, South Africa, 10–15 August 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Banon, South.; Diaz, P.; Rodriguez, Grand.; Delores Garrido, M.; Price, A. Ascorbate, green tea and grape seed extracts increase the shelf life of low sulfite beef patties. Meat Sci. 2007, 77, 626–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ismail, H.A.; Lee, Eastward.J.; Ko, Grand.Y.; Paik, H.D.; Ahn, D.U. Effect of antioxidant application methods on the color, lipid oxidation and volatiles of irradiated ground beef. J. Food Sci. 2009, 74, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, A.K.; Anjaneyulu, A.S.R.; Kondaiah, Northward. Evolution of reduced beany flavor full-fat soy paste for comminuted meat products. J. Food Sci. 2006, 71, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, One thousand.; Cienfuegos, C.; Guinard, J.X. The Flexitarian Flip™ in university dining venues: Pupil and developed consumer acceptance of mixed dishes in which brute protein has been partially replaced with plant protein. Food Qual. Adopt. 2018, 68, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, G.; Guinard, J.10. The flexitarian Flip™: Testing the modalities of season as sensory strategies to achieve the shift from meat-centered to vegetable-forward mixed dishes. J. Food Sci. 2018, 83, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, Chiliad. Consumer acceptance of blending plant-based ingredients into traditional meat-based foods: Prove from the meat-mushroom alloy. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 79, 103758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elzerman, J.E.; Hoek, A.C.; van Boekel, M.A.J.Due south.; Luning, P.A. Consumer acceptance and appropriateness of meat substitutes in a meal context. Food Qual. Prefer. 2011, 22, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville, Yard.; Tarrega, A.; Hewson, 50.; Foster, T. Consumer-orientated evolution of hybrid beef burger and sausage analogues. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, v, 852–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoek, A.; Elzerman, J.E.; Hageman, R.; Kok, F.J.; Luning, P.A.; de Graaf, C. Are meat substitutes liked better over time? A repeated in dwelling utilise exam with meat substitutes or meat in meals. Food Qual. Prefer. 2013, 28, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megido, R.C.; Gierts, C.; Blecker, C.; Brostaux, Y.; Haubruge, É.; Alabi, T.; Francis, F. Consumer acceptance of insect-based alternative meat products in Western countries. Food Qual. Prefer. 2016, 52, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kris-Etherton, P.; Feming, J.; Harris, West.S. The debate about n-six polyunsaturated fatty acid recommendations for cardiovascular health. J. Am. Nutrition. Assoc. 2010, 110, 201–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, J.; Chisolm, A. Chapter xx: Cardiovascular diseases. In Essentials of Human Nutrition, 3rd ed.; Isle of man, J., Truswell, A.S., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, United states of america, 2007; pp. 282–285, 288–289. [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay, G.C.; Hevner, A.R.; Berndt, D.J. The use of focus groups. In Design Science Inquiry, Design Enquiry in Data Systems; Integrated Series in Information Systems; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 121–143. [Google Scholar]

- Rabiee, F. Focus-grouping interview and data analysis. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2004, 63, 655–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackham, T.M.; Stevenson, L.; Abayomi, J.C.; Davie, I.One thousand. Consumers' knowledge and attitudes to takeaway nutrient in Merseyside. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2016, 75, E91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richi, E.B.; Baumer, B.; Conrad, B.; Darioli, R.; Schmid, A.; Keller, U. Review Wellness Risks Associated with Meat Consumption: A Review of Epidemiological Studies. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2015, 85, 70–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berghofer, E.; Grzeskowiak, B.; Mundigler, N.; Sentall, W.B.; Walcak, J. Antioxidative backdrop of fababean-, soybean- and oat tempeh. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 1998, 49, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, A.G.; Mubarak, A.E.; El-Beltagy, A.E. Nutritional potential and functional properties of tempe produced from mixture of different legumes. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2008, 43, 1754–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troy, D.J.; Kerry, J.P. Consumer Perception and the role of science in the meat industry. Meat Sci. 2010, 86, 214–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, S.One thousand.; Morgan, J.B.; Wulf, D.M.; Tatum, J.D.; Williams, Due south.Due north.; Smith, One thousand.C. Vitamin E supplementation of cattle and shelf life of beefiness for the Japanese market. J. Anim. Sci. 1997, 75, 2634–2640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hough, Yard.; Wakeling, I.; Mucci, A.; Chambers, I.V.E.; Mendez Gallardo, I.; Rangel Alves, 50. Number of consumers necessary for sensory acceptability tests. J. Food Qual. Prefer. 2006, 17, 522–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, W.; Worsley, T. Understanding the older food consumer: Present mean solar day behaviours and futurity expectations. Ambition 2009, 52, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ming, T.T.; Bin Ismail, H.; Rasiah, D. Hierarchical concatenation of consumer-based make equity: Review from the fast nutrient manufacture. Int. Omnibus. Econ. Res. J. 2011, x, 67–80. [Google Scholar]

- Tamuliene, V. Consumer mental attitude to fast food: The case study of Lithuania. Res. Rural Dev. 2015, ii, 255–261. [Google Scholar]

- Min, J.; Jahns, Fifty.; Xue, H.; Kandiah, J.; Wang, Y. Americans' perceptions well-nigh fast food and how they associate with its consumption and obesity risk. Adv. Nutr. 2018, 9, 590–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Barcellos, M.D.; Kugler, J.O.; Grunert, K.One thousand.; Van Wezemael, L.; Perez-Cueto, F.J.A.; Ueland, O.; Verbeke, W. European consumers' credence of beef processing technologies: A focus group report. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2010, 11, 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wezemael, L.; Verbeke, Due west.; de Barcellos, 1000.D.; Scholderer, J.; Perez-Cueto, F. Consumer perceptions of beefiness healthiness: Results from a qualitative written report in iv European countries. BMC Public Health 2010, x, 835–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidigal MC, T.R.; Minim, V.P.; Simiqueli, A.A.; Souza PH, P.; Balbino, D.F.; Minim, L.A. Food engineering neophobia and consumer attitudes toward foods produced by new and conventional technologies: A example study in Brazil. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 60, 832–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Wu, 50.; Chen, X.; Huang, Z.; Hu, W. Effects of nutrient-condiment-information on consumers' willingness to accept nutrient with additives. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, xv, 2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bech-Larsen, T.; Grunert, K.G. The perceived healthiness of functional foods: A conjoint study of Danish, Finnish and American consumers' perceptions of functional foods. Appetite 2003, 40, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.J.; McNaughton, S.A.; Gall, S.50.; Blizzard, L.; Dwyer, T.; Venn, A.J. Takeaway food consumption and its associations with diet quality and intestinal obesity: A cross-sectional report of young adults. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Deed. 2009, 6, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labrecque, J.; Doyon, Yard.; Bellavance, F.; Kolodinsky, J. Acceptance of Functional Foods: A comparison of French, American and Canadian consumers. Tin can. J. Agric. Econ. 2006, 54, 647–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angor, Grand.M.; Al-Abdullah, B.M. Attributes of depression-fat beef burgers aimed at enhancing product quality. J. Muscle Foods 2010, 21, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz-Turp, G.; Serdaroglu, M. Effects of using plum puree on some properties of low fat beef patties. Meat Sci. 2010, 86, 896–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, B.; Miranda, J.M.; Vasquez, B.I.; Fente, C.A.; Franco, C.1000.; Rodriguez, J.L.; Cepeda, A. Development of a hamburger patty with healthier lipid formulation and study of its nutritional, sensory and stability properties. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2012, 5, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawashin, D.M.; Al-Juhaimi, F.; Mohamed Ahmed, I.A.; Ghafoor, K.; Babiker, E.E. Physicochemical, microbiological, and sensory evaluation of beef patties incorporated with destoned olive block pulverization. Meat Sci. 2016, 122, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzon, G.A.; McKeith, F.K.; Gooding, J.P.; Felker, F.C.; Palmquist, D.Due east.; Brewer, Grand.S. Characteristics of low-fatty beefiness patties formulated with carbohydrate-lipid composites. J. Nutrient Sci. 2003, 68, 2050–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candogan, K. The issue of tomato paste on some quality characteristics of beef patties during refrigerated storage. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2002, 215, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.-C.; Zayas, J.F.; Bowers, J.A. Functional properties of sorghum powder as an extender in beefiness patties. J. Food Qual. 1999, 22, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twigg, G.One thousand.; Kotula, A.W.; Immature, East.P. Consumer credence of beef patties containing soy protein. J. Anim. Sci. 1977, 44, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babji, A.South.; Abdullah, A.; Fatimah, Y. Gustation panel evaluation and acceptance of soy-beef burger. Pertanika 1986, 9, 225–233. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, One thousand.Northward.; Human being, D.I.; Egbert, W.R.; Mccaskey, T.A.; Liu, C.West. Soy protein and oil effects on chemic, concrete and microbial stability of lean ground-beefiness patties. J. Food Sci. 1991, 56, 906–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deliza, R.; Saldivar, South.O.Due south.; Germani, R.; Benassi, V.T.; Cabral, L.C. The effects of colored textured soybean protein (tsp) on sensory and physical attributes of footing beef patties. J. Sens. Stud. 2002, 17, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassem, G.M.A.; Emara, K.Yard.T. Quality and acceptability of value-added beefiness burger. Earth J. Dairy Nutrient Sci. 2010, v, 14–20. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1. Sensory aspect scores of five beef patties substituted by tempeh at dissimilar levels. The patties were evaluated during focus groups (A = focus group 1 and B = focus group two). a–c Inside each sensory attribute, bars that practice not share the same superscripts are significantly unlike (p < 0.05).

Figure ane. Sensory attribute scores of v beef patties substituted by tempeh at different levels. The patties were evaluated during focus groups (A = focus group 1 and B = focus group 2). a–c Within each sensory attribute, confined that practice not share the aforementioned superscripts are significantly different (p < 0.05).

Effigy 2. Sensory attribute scores of 5 raw beefiness patties substituted past tempeh at dissimilar levels. The patties were evaluated by focus groups (northward = 15). a–c Inside each sensory attribute, bars that do non share the same superscripts are significantly different (p < 0.05).

Figure 2. Sensory attribute scores of five raw beef patties substituted past tempeh at different levels. The patties were evaluated past focus groups (n = 15). a–c Within each sensory aspect, confined that exercise not share the aforementioned superscripts are significantly different (p < 0.05).

Table 1. Limerick of the v patty treatments.

Tabular array 1. Composition of the five patty treatments.

| Treatment | Lean Meat (%) | Fat (%) | Tempeh (%) | Bread Crumb (%) | Table salt (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 89 | 10 | - | - | ane |

| Bread nibble 10% | 79 | x | - | x | 1 |

| Tempeh 10% | 79 | 10 | 10 | - | ane |

| Tempeh xx% | 69 | x | 20 | - | 1 |

| Tempeh 30% | 59 | ten | 30 | - | 1 |

Tabular array 2. Summary of the characteristics of focus group participants.

Table 2. Summary of the characteristics of focus group participants.

| Focus Group | Number of Participants | Number of Participants | Number of Participants | Number of Participants | Number of Participants | Number of Participants | Gender Male person/Female |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age ≤xviii | Age xix–25 | Age 25–30 | Historic period 30–40 | Age 40–50 | Age ≥l | ||

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | iv/3 |

| 2 | 2 | vi | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4/4 |

| Total | 2 | seven | 3 | 1 | ane | 1 | 8/7 |

Table 3. Gender and age grouping composition of the consumer sensory experiment.

Tabular array 3. Gender and historic period grouping composition of the consumer sensory experiment.

| Gender | Age Category | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18–24 | 25–30 | 31–40 | 41–fifty | >50 | Total | |

| Male person | 17 | 12 | 8 | half dozen | 5 | 48 |

| Female | 26 | viii | 16 | x | 10 | 70 |

| Full | 43 | xx | 24 | 16 | 15 | 118 |

Tabular array 4. Mean scores for sensory attributes for 5 beef patties substituted by tempeh at different levels in the pilot sensory written report. The patties were evaluated by a small number of panelists (north = 14). a–c Inside each row, means that do not share the aforementioned letters are significantly different (p < 0.05).

Table 4. Mean scores for sensory attributes for five beef patties substituted by tempeh at different levels in the airplane pilot sensory study. The patties were evaluated by a small number of panelists (n = fourteen). a–c Inside each row, ways that do not share the aforementioned messages are significantly unlike (p < 0.05).

| Command | Staff of life Nibble ten% | Tempeh 10% | Tempeh twenty% | Tempeh 30% | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall acceptability | iv.21 | 4.21 | 3.93 | 3.5 | two.93 | 0.155 |

| Intensity of non-beef odors | 1.71 a | 2.57 a,b | 2.43 a,b | ii.57 a,b | 3.00 b | 0.045 |

| Intensity of beef olfactory property | iv.66 a | iv.10 a,b | iii.94 a,b | three.02 b | 2.11 c | 0.000 |

| Tenderness | ii.79 a | iv.29 c | 2.86 a,b | 4.00 c | iii.79 b,c | 0.000 |

| Chewiness | 2.57 a | three.86 b | ii.36 a | 3.57 b | 3.57 b | 0.000 |

| Juiciness | 2.57 | 3.21 | 2.36 | three.14 | 2.50 | 0.088 |

| Flavor intensity | iii.57 | 3.29 | 3.43 | 3.v | 3.3 six | 0.802 |

| Non-beefiness flavor | 1.86 a | 2.l a,b | two.64 a,b | ii.64 a,b | three.43 b | 0.007 |

| Acceptance of flavor | 4.29 | 4.36 | 3.29 | 3.71 | 3.00 | 0.110 |

Tabular array five. Hateful scores for sensory attributes of five beefiness patties substituted by tempeh at different levels in the pilot sensory study. The patties were evaluated by a minor number of panelists (n = 14). a–c Within each row, means that do not share the same letters are significantly different (p < 0.05).

Table v. Hateful scores for sensory attributes of five beef patties substituted past tempeh at different levels in the airplane pilot sensory study. The patties were evaluated by a small number of panelists (north = fourteen). a–c Within each row, ways that exercise non share the same letters are significantly different (p < 0.05).

| Control | Breadstuff Crumb 10% | Tempeh 10% | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall acceptability | 5.42 | 5.44 | 5.38 | 0.97 |

| Beefiness odor | 4.19 a | 3.53 b | three.78 b | 0.00 |

| Tenderness | 3.23 c | 4.64 a | four.fourteen b | 0.00 |

| Chewiness | ii.65 c | 4.05 a | 3.43 b | 0.00 |

| Juiciness | 3.66 b | 3.95 ab | 4.ten a | 0.04 |

| Flavor intensity | 4.31 | 4.32 | 4.25 | 0.81 |

| Not-beef season | 2.43 b | iii.41 a | three.xi a | 0.00 |

| Acceptance of flavor | 5.62 | 5.60 | 5.42 | 0.64 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access commodity distributed under the terms and atmospheric condition of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/iv.0/).

Source: https://www.mdpi.com/2304-8158/9/1/63/htm

0 Response to "What Kind of Consumer Is a Human When They Eat the Beef Out of a Patty"

Post a Comment